BENIGN ACUTE CHILDHOOD MYOSITIS

A stiff-legged gait

Luciano Schiazza M.D.

Dermatologist

c/o InMedica - Centro Medico Polispecialistico

Largo XII Ottobre 62

cell 335.655.97.70 - office 010 5701818

www.lucianoschiazza.it

Benign acute childhood myositis (BACM) is a rare, transient, acute, self-limiting muscle disorder classically affecting school-aged children (primarily boys, within the age range of 3–14 years old) during times of influenza outbreaks and epidemics (in the late winter and early spring).

It most commonly occurs after influenza B and occasionally influenza A infection, but parainfluenza, adenovirus, herpes simplex, Epstein-Barr, Coxsackie, rotavirus, and M pneumoniae have also been implicated.

Benign acute childhood myositis (BACM) was first described in 1957 by Lundberg in Sweden patients under the name of “Myalgia Cruris Epidemica”.

Clinical presentation

Typical clinical presentation of BACM shows a school aged boy presenting with bilateral calf pain and compensatory gait. The myositis has preceded by URI (upper respiratory infection) symptoms (fever, malaise, cough, sore throat, headache, and rhinitis) consistent with an uncomplicated viral influenza infection during influenza season.

The myositis usually appears as the flu-like symptoms (particularly fever) subside (during the early recovery phase of the virus) (approximately 5 days). The boy is afebrile with normal vital signs. He typically complains of sudden, acute bilateral calf pain (localized to gastrocnemius-soleus muscles), tenderness, weakness and discomfort in the lower legs that are so severe that is unable to ambulate (secondary to pain). So he may refuse to walk (crawling or “bottom shuffling”) or use, to avoid stretching the calf muscles, a characteristic broad-based and stiff-legged posture with shuffling gait (so called “ Frankenstein gait”) or "toe-walking" (photo).

Neurologic examination is normal.

At rest, the patient keeps his feet at a position of slight plantar flexion; passive dorsiflexion at the ankles elicited pain.

Physical examination generally shows in the lower extremities normal strength when the patient is lying down, normal tone and deep tendon reflexes and sensitivity and no neurologic deficits.

Laboratory investigations show markedly elevated serum creatinine kinase (CPK) level, normal leucocyte count, platelet count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, no myoglobinuria an acute renal failure.

About muscle biopsy, the three main typical features, namely characteristic calf tenderness with gait abnormalities or even refusal to walk and raised CK associated with URI history, can prevent it. When it has been performed during the symptomatic phase it revealed evidence of muscle necrosis and muscle fiber regeneration, with mild infiltration of polymorphonuclear or mononuclear leukocytes.

BACM usually has no progression or complications. The hallmark of BACM is spontaneous and rapid full clinical recovery (no residual impairment and no recurrence of pain or weakness in the lower extremities) within 3-10 days, with resolution of the elevated muscle enzymes within three weeks. Only rest and minimal supportive measures are required.

Daily physical examination and urine dipstick during acute phase are sufficient to promptly detect complications and rule out more severe illnesses (rhabdomyolisis). Urine appears dark (reddish brown, Coca-Cola colored) when myoglobin is filtered into the urine, and will dip positive for blood because of the cross reactivity of haem and myoglobin. Creatine kinase (CK) should be measured only at diagnosis in order to early exclude degenerative diseases.

Recurrence is rare and has been demonstrated to be caused by different viruses or different influenza types

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism by which myositis occurs is controversial. Current theories are that damage occurs via immune-mediated processes initiated by viral hosts or that the virus particles themselves invade the muscle tissue to cause damage. But generally, such biopsies show nonspecific degenerative changes and muscle necrosis.

Viral studies show that influenza B is more likely than influenza A to cause myositis, likely due to the presence of NB protein in the membrane of influenza B, which is implicated in viral entry and may have myotrophic properties.

Myositis occurs only in a small percent of those affected with influenza (genetic predisposition?), and is most common in children (mean age eight years), possibly because of virus tropism for immature muscle cells.

Key elements in the diagnosis

-

time scale of the illness (a preceding upper respiratory infection followed by the acute onset of typical myositis clinical findings, predominantly affecting gastrocnemius-soleus muscles)

-

history of contacts

-

school-aged boys

-

late winter–early spring predominance,

-

elevated CK (usually up to 2 to 50 times normal), and aminotransferase levels (especially AST)

-

transient hematological abnormalities (mild leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia).

-

erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP are usually normal but may be mildly elevated.

Findings not classically associated with BACM include

-

myoglobinuria,

-

recent trauma or vigorous exercise,

-

family history of neuromuscular disorders,

-

subacute or chronic progression,

-

rash,

-

frank muscle weakness,

-

or abnormal neurologic findings.

When such atypical features are present, for failure to weight-bear in pediatric population, despite a suggestive clinical picture, further investigation is required and key differential diagnoses should be considered.

So, a child that refuses to walk or to weight-bear may be due

- to a neurological deficit, i.e. lower extremity weakness

- or may be a protective reaction, i.e. to avoid muscle pain

Acute muscle pain and walking difficulty are symptoms compatible with both benign and severe degenerative diseases, and the onset sometimes may be mistaken for very severe neurological illness such as Guillain–Barrè syndrome or chronic autoimmune diseases.

Differential diagnosis

Rhabdomyolysis

Rhabdomyolysis is the most severe in the spectrum of myositis because of possible life-threatening complications (myoglobin-induced acute renal failure, compartment syndrome and electrolyte disturbances) due to release into the systemic circulation of damaged skeletal muscle cells. Haem protein myoglobin and the enzyme creatine kinase (CK) are diagnostic markers for the illness: urine appears reddish brown when myoglobin is filtered into the urine, and will dip positive for blood because of the cross reactivity of haem and myoglobin. But urine microscopic examination don’t show red blood cells. Epidemiologically, rhabdomyolysis has been observed more frequently in girls and has been associated with influenza A (linked with more severe cases).

Key points

-

Acute onset

-

Recent injury

-

Muscle pain, typically most prominent in proximal muscle groups, such as the thigs and shoulders, and in lower back and calves

-

Weakness

-

Dark (red to brown) urine

-

Ck elevated

Guillain-Barré syndrome

It is an important differential diagnosis. It is a peripheral neuropathy characterized by a rapidly progressive limb weakness, associated with a history of preceding respiratory or gastrointestinal infection. Neurologic examination reveals loss of the deep tendon reflexes, sensory symptoms such as paraesthesia), autonomic signs such as. tachycardia, and cranial nerve involvement ( facial weakness).

Key points

-

Acute onset after 2-4 respiratory or gastrointestinal viral febrile illness,

-

loss or decreased deep tendon reflexes in the lower extremities,

-

distal paraesthesia,

-

symmetric progressive lower extremity muscle weakness ascending over time,

-

facial weakness (cranial nerve involvement)

-

tachycardia

-

normal CPK

Juvenile dermatomyositis

JDMis a systemic, autoimmune inflammatory disorder that primarily affects the skin and the skeletal muscles in children younger than 18 years.

Myopathy is characterized by:

-

Proximal muscle weakness

-

Extensor muscles often more affected than the flexor muscles

-

Muscle fatigue/weakness when climbing stairs, walking,

-

Difficulty rising from a seated or supine position without support

-

Difficulty combing hair, or reaching for items above shoulders

-

Distal strength, sensation, and tendon reflexes maintained

Cutaneous findings are characterized by:

-

heliotrope rash: purplish discoloration along the hairline and malar region of the face and eyelids (with the color of a garden perennial)

-

Gottron’s papules: eruption of shiny, elevated, violaceous papule and plaques primarily over the metacarpophalangeal joints and proximal, interphalangeal joints with sparing of the interphalangeal spaces.

-

Changes in the nailfolds of the fingers (ragged cuticles and prominent blood vessels on nail folds)

-

V-neck sign: violaceous erythema or poikiloderma around face, neck and anterior chest.

-

shawl sign: diffuse, flat, violaceous erythema or poikiloderma of the upper back and shoulders.

-

Erythematous, violaceous scaly plaques on the extensor surfaces of the extremities

-

Mechanic’s hands, characterized by cracking commonly of the first, second and third fingers pad skin.

-

Subcutaneous calcinosis (30-70% cases of JDM)

Laboratory investigations show:

-

typical findings on muscle MRI and ultrasonography

-

nailfold capillaroscopy abnormalities

-

elevated muscle enzymes (CPK)

-

myopathic changes on electromyography

-

abnormal muscle biopsy findings

The etiology of JDM is probably linked to an interplay of the immune system and enviromnmental triggers (seasonal clusters in April and May, and infectious agents – Coxsackie B virus, Parvovirus B19, Enteroviruses, Streptococcus species)

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

-

Either insidious presentation over month or abrupt disease onset

-

Swelling, tenderness and stiffness in joints worsening in the morning, with articular flexion

-

predominantly asymmetric distribution

-

Spiking fevers occurring once or twice each day at about the same time of day

-

Evanescent rash on the trunk and extremities evanescent rash (lasting a few hours), which is typically nonpruritic, macular, and salmon colored. Occasionally, the rash is extremely pruritic and resistant to antihistamine treatment.

Muscular dystrophy

-

positive family history,

-

absent tendon reflexes,

-

chronic symptoms,

-

muscle weakness proximal before distal

-

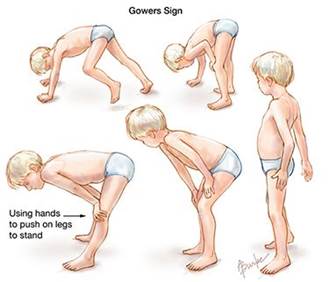

wadding gait(exaggerated alternation of lateral trunk movements with an exaggerated elevation of the hip, suggesting the gait of a duck)

-

Gower’s sign(it indicates weakness of the proximal muscles, namely those of the lower limb. The patient has to use their hands and arms to "walk" up their own body from a squatting position due to lack of hip and thigh muscle strength)