Reiter syndrome / Reactive arthritis

Luciano Schiazza M.D.

Dermatologist

c/o InMedica - Centro Medico Polispecialistico

Largo XII Ottobre 62

cell 335.655.97.70 - office 010 5701818

www.lucianoschiazza.it

Reiter syndrome (Rs)/Reactive arthritis (ReA) is a painful form of inflammatory arthritis that develops in reaction and in response to an infection of certain bacteria or virus (trigger) that started somewhere else in another part of the body (cross-reactivity) often in intestines (gastrointestinal-GI), genitals or urinary tract (GU).

German physician Hans Conrad Julius Reiter described the condition in a soldier he treated during World War I.

The term "reactive arthritis" is increasingly used as a substitute for this designation because of Hans Conrad Julius Reiter'sNazi Party affiliation, and in particular his involvement in forced human experimentation in the Buchenwald concentration camp (which, after his capture at the end of World War II, resulted in his prosecution in Nuremberg as awar criminal).

It most commonly strikes individuals aged 20–40 years of age, is more common in men than in women, and more common in white than in black people, owing to the high frequency of the HLA-B27 gene in the white population. Reactive arthritis tends to occur most often in men between ages 20 and 50. Most cases of reactive arthritis appear as a short episode. Occasionally, it becomes chronic.

Patients with HIV have an increased risk of developing reactive arthritis as well. Patients with new-onset ReA must be evaluated for HIV. HIV-positive ReA patients are at risk for severe psoriasiform dermatitis, which commonly involves the flexures, scalp, palms, and soles. Because of the disturbances of immune homeostasis in AIDS.

Because common systems involved include the eye, the urinary system, and the hands and feet, one clinical mnemonic in reactive arthritis is "Can't see, can't pee, can't climb a tree."

The Reiter syndrome/reactive arthritis is classically characterized by the triad of symptoms:

-

Nongonococcal, noninfectious urethritis

-

Inflammatory asymmetric oligoarthritis

-

Conjunctivitis

But it has been suggested, however, that the syndrome is better described as a triad consisting of arthritis of large joints, conjunctivitis or iridocyclitis, and nonbacterial urethritis in men or cervicitis in women. Some prefer to describe it as a tetrad, adding mucocutaneous lesions, as well as psoriasis-like skin lesions such as circinate balanitis and keratoderma blennorrhagicum to the classic triad.

In this view, the complete and incomplete forms of ReA can be identified by the presence or absence of the mucocutaneous involvement.

But not all affected persons have all the manifestations and the classic triad occurs in only about one third of patients at onset.

Less stringent diagnostic criteria from the American College of Rheumatology have specified a 1-month duration of arthritis in association with genitourinary (GU) infection (urethritis, cervicitis, or both) (especially with Chlamydia trachomatis).

By the time the patient presents with symptoms, often the “trigger” infection has been cure or is in remission in chronic cases.

Rs/ReA is usually triggered by a GU or GI infection and thus is sometimes classified as venereal or dysenteric. Such infections are mostly the result of gram-negative, obligate, or facultative intracellular pathogens. Organisms that have been associated with ReA include the following:

-

C trachomatis (L2b serotype)

-

Ureaplasma urealyticum

-

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

-

Shigella flexneri

-

Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and Hadar

-

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

-

Cyclospora

-

Yersinia enterocolitica and pseudotuberculosis

-

Campylobacter jejuniand coli

-

Clostridium difficile

-

Beta-hemolytic (eg, group A) and viridans streptococci

| Etiologic Agents in Postenteric Reactive Arthritis | |

|---|---|

| Common | Uncommon |

| Shigella flexneri | Shigella sonnei |

| Salmonella typhimurium | Shigella dysenteriae |

| Salmonella enteritidis | Salmonella paratyphi B |

| Yersinia enterocolitica O3 | Salmonella paratyphi C |

| Yersinia enterocolitica O9 | Yersinia enterocolitica O8 |

| Yersinia pseudotuberculosis | Giardia lamblia |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Group A streptococci (?) |

Reactive arthritis isn't contagious. However, the bacteria that cause it can be transmitted sexually or in contaminated food. But only a few of the people who are exposed to these bacteria develop reactive arthritis.

Besides using condoms during sexual activity, there is no known preventative measure for reactive arthritis.

In sexually active males, most cases of reactive arthritis follow infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or Ureaplasma urealyticum, both sexually transmitted diseases.

Asymptomatic chlamydial infections might be a common cause and chlamydial ReA is propbably underdiagnosed. An important difference between Chlamydia -induced (postvenereal) ReA and postenteric ReA is the presence of viable but aberrant chlamydial organisms in the synovial fluid(so-called Chlamydia persistence). PCR assay to detect C trachomatis DNA in synovial samples may be a good method for establishing the diagnosis of Chlamydia -induced arthritis in patients with ReA.

The frequency of ReA after these enteric infections is about 1%-4%. The enteric pathogens that most commonly result in ReA are Campylobacter (C jejuni, 90-95%; C coli, 5-10%) and Shigella. Other pathogens include Salmonella, Yersinia, C difficile, E coli and Helicobacter pylori. Some patients with ReA continue with intermittent bouts of diarrhea and abdominal pain. Although enteritis is usually a prolonged diarrheal episode, it can also manifest as a 24-hour episode of increased bowel activity.

Group A streptococci are known to be capable of causing poststreptococcal ReA.Patients with this condition demonstrate increase antistreptolysin O (ASO) antibodies and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).ReA can also be induced by tonsillitis.

Acute tuberculosis can sometimes cause ReA. The resulting condition is known as Poncet disease, which is a different entity from tuberculous arthritis.

Other possible linkages include infection with C difficileand with bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). ReA has also been shown to occur after tetanus and rabies vaccination.

| Percent Sensitivity and Specificity guidelines of Various Criteria for Typical Reiter's Syndrome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Method of diagnosis | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| Episode of arthritis of more than 1 month with urethritis and/or cervicitis | 84.3% | 98.2% |

| Episode of arthritis of more than 1 month and either urethritis or cervicitis, or bilateral conjunctivitis | 85.5% | 96.4% |

| Episode of arthritis, conjunctivitis, and urethritis | 50.6% | 98.8% |

| Episode of arthritis of more than 1 month, conjunctivitis, and urethritis | 48.2% | 98.8% |

The onset of ReA is usually acute and characterized by malaise, fatigue, and fever.

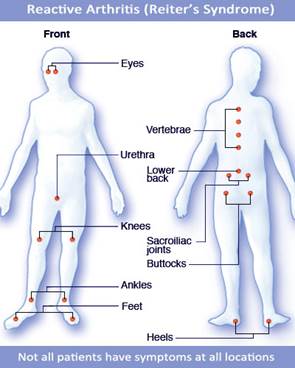

An asymmetrical, predominately lower-extremity, monoarthritis/oligoarthritis is the major presenting symptom. Myalgias may be noted early on. Asymmetric arthralgia and joint stiffness consists of an inflammation of fewer than five joints which primarily includes the knees, ankles, and feet (the wrists may be an early target). Low-back pain (sacroiliac joint) occurs in 50% of patients. The arthritis may be "additive" (more joints become inflamed in addition to the primarily affected one) or "migratory" (new joints become inflamed after the initially inflamed site has already improved).

An asymmetrical inflammatory arthritis of interphalangeal joints may be present but with relative sparing of small joints such as the wrist and hand.

Heel pain associated with enthesitis that involve the Achilles tendon and plantar fasciitis is also common.

Reactive arthritis (ReA) usually develops 2-4 weeks after a genitourinary (GU) or gastrointestinal (GI) infection (or, possibly, a chlamydial respiratory infection). About 10% of patients do not have a preceding symptomatic infection.

The classic triad of symptoms—noninfectious urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis—is found in only one third of patients with ReA and has a sensitivity of 50.6% and a specificity of 98.9%.

In postenteric ReA, diarrhea and dysenteric syndrome (usually mild) is commonly followed by the clinical triad in 1-4 weeks Duration of diarrhea and weight loss are also considered risk factors in the development of ReA after enteric infections.

Diagnosing Reiter’s disease can be difficult because of the great variation of the clinical features and because the classical triad is present in only one third of the patient. Diagnosis is made according to the typical history, clinical symptoms and the findings of laboratory tests.

Certain factors increase your risk of reactive arthritis:

- Age. Rs/ReA is most common in young men, with the peak onset in the third decade of life. It rarely occurs in children; when it does, the enteric form of the disease is predominant. Most pediatric patients present with symptoms after the age of 9 years.

- Gender/sex. Women and men are equally likely to develop reactive arthritis in reaction to foodborne enteric infections. However, men are more likely than are women to develop reactive arthritis in response to sexually transmitted bacteria.

- Genetics/Hereditary factors. A specific genetic marker (a paricular defective gene) has been linked to reactive arthritis. But many people who have this marker never develop reactive arthritis.

ReA has an important genetic component: it is strongly associated with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–B27 (HLA-B27) haplotype on chromosone 6 (positive in 65-96% of patients -average, 75%, almost exclusively males) an MHC class I molecule involved in T-cell antigen presentation. and is classified in the category of seronegative spondyloarthropathies, which includes ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, the arthropathy of associated inflammatory bowel disease, juvenile-onset ankylosing spondylitis, juvenile chronic arthritis, and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis.

Patients with HLA-B27, as well as those with a strong family clustering of the disease, tend to develop more severe and long-term disease.

HLA-B27 may share molecular characteristics with bacterial epitopes, facilitating an autoimmune cross-reaction instrumental in pathogenesis. HLA-B27 contributes to the pathogenesis of the disease and reportedly increases the risk of ReA 50-fold.HLA-B51 and HLA-DRB1 alleles have also been shown to be associated with ReA.

The frequency of ReA appears to be related to the prevalence of HLA-B27 in the population. As with other spondyloarthropathies, HLA-B27 and ReA are more common in white people than in black people. When ReA occurs in black persons, it is frequently B27-negative.

The classic triad of ReA symptoms (found in only one third of patients) consists of the following:

-

Noninfectious urethritis

-

Arthritis

-

Conjunctivitis

Physical Examination

Usually, the disease starts within 4 weeks after infection. Patients may experience any number of features, including generalized symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and weight loss, and urogenital, rheumatologic, ophthalmologic, dermatologic, and rarely visceral manifestations.

A scoring system for diagnostic points in ReA-like spondyloarthropathies exists. In this system, the presence of 2 or more of the following points (1 of which must pertain to the musculoskeletal system) establishes the diagnosis:

-

Asymmetric oligoarthritis, predominantly of the lower extremity

-

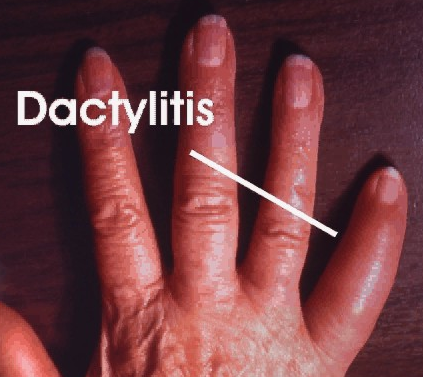

Sausage-shaped finger (dactylitis), toe or heel pain, or other enthesitis

-

Cervicitis or acute diarrhea within 1 month of the onset of arthritis

-

Conjunctivitis or iritis

-

Genital ulceration or urethritis

Diagnosis is made by medical history and clinical findings, but symptoms taken individually cannot diagnose the disease

Physical findings in genitourinary tract include:

Genitourinary tract, (GU) tract

The classical presentation of the syndrome starts with urinary symptoms such as burning pain on urination (dysuria) or an increased frequency of urination.

Urogenital symptoms may be primary or postdysenteric and may include the following target-organ:

-

Prostate, urethra and penis in men (prostatis, urethritis,

-

Fallopian tubes, uterus, cervix, vagina and urethra in women (cystitis, vulvovaginitis, cervicitis, bartholinitis, cystitis, salpingo-oophoritis)

-

Proctitis in men and women who practice receptive anal intercourse.

Urethritis

Both postvenereal and postenteric forms of ReA may manifest initially as nongonococcal urethritis, with frequency, dysuria, urgency, and urethral discharge; this urethritis may be mild or inapparent. Urogenital symptoms, whether resulting from GU infection or from GI infection, are found in 90% of patients with ReA, but an estimated 0.5-1% of cases of urethritis evolve into ReA.

Often, the initial urethritis is treated with antibiotics (especially wide-spectrum tetracyclines or macrolides) when findings suggest gonorrhea. Despite an apparent early cure, the manifestations of the disease appear several weeks later, and the patient may not relate them to a previous episode of urethritis.

Urethritis develops acutely 1-2 weeks after infection through sexual contact and is similar to gonococcal urethritis.

A purulent or hemopurulent exudate appears, and the patient complains of burning pain on passing urine (dysuria) or an increased frequency of urination.

In men, chlamydial urethritis is less painful and produces less purulent discharge (usually clear mucoid discharge especially in the morning) than acute gonorrhea does, associated with meatal edema and erythema. Coinfection with Chlamydia and Neisseria organisms is common in some areas.

In women, urethritis and cervicitis may be mild, with dysuria or slight vaginal discharge, or asymptomatic.

Urethritis is difficult to diagnose in children but is present in 30% of pediatric patients at onset. Obtaining a history of dysuria from children is difficult, possibly because the urinary abnormality is mild or absent. In patients with painless discharge, staining of the underpants may be evident.

In man, inflammation of the prostate gland (prostatitis) may cause fever, chills and tenderness (up to 80%).

Circinate balanitis, consists of small shallow painless ulcers of the urethral meatus or the glans penis. The condition is characterized by circinate or gyrate white plaques that grow centrifugally and eventually cover the entire surface of the glans penis. The penile shaft and scrotum can be involved. On an uncircumcised penis, the lesions typically remain moist; on a circumcised penis, they may harden and crust, causing pain and scarring in 50% of patients.

webmd.ads2.defineAd({id:'ads-pos-420',pos: 420}); Lymphogranuloma venereum infection may be asymptomatic; screening should be considered in all men who have sex with men (MSM) presenting with acute arthritis, particularly if they are infected with HIV.

Musculoskeletal system

The classic joints that become inflamed in RA are the knees, ankles, feet, wrists, sacroiliac joints and, less commonly, spine joints. The particular joints involved are usually asymmetric, that is, one side of the body or the other is affected, rather than both sides simultaneously.

The inflammation leads to stiffness, pain, swelling, warmth, and redness of the joints involved. Patients may develop inflammation of entire fingers or toes which can give the appearance of a “sausage digit.” The arthritis of RA can be associated with inflammation of the spine, leading to stiffness and pain in the back or neck.

Cartilage can also become inflamed, especially around the breastbone where the ribs meet in the front of the chest, this condition is called costochondritis.

Muscles attach to the bones by tendons. In RA, the tendon insertion points can become inflamed (tendonitis), tender, and painful when exercised.

Articular involvement in ReA is typically asymmetric and usually affects the weight-bearing joints (ie, knees, ankles, and hips), but the shoulders, wrists, and elbows may also be affected. In more chronic and severe cases, the small joints of the hands and feet may be involved as well. Dactylitis (ie, sausage digits) may develop.

The arthritis may be “additive” (more joints become inflamed in addition to the primarily affected one or migratory (new joints become inflamed after the initially inflamed site has been already improved).

Multiple joint involvement is common, usually affecting the knees or feet. Joints symptoms develop 2-4 weeks after urogenital infection, but 10% of affected individuals have no history of urethritis. Conjunctivitis and associated iritis and uveitis usually develop after the arthritis.

Reactive arthritis can affect the heels, toes, fingers, low back, and joints, especially of the knees or ankles. Though it often goes away on its own, reactive arthritis can be prolonged and severe.

In children, joint involvement is oligoarticular in 69% of cases, polyarticular in 27%, and monoarticular in 4%.

Joints are commonly described as tender, warm, swollen, and, sometimes, red. Symptoms may occur initially or several weeks after onset of other symptoms.

Migratory or symmetric involvement is also reported. Periostitis and tendinitis may occur, especially involving the Achilles tendon, which produces pain in the heel.

The arthritis is usually remittent and rarely leads to severe limitation of functional capacity. Muscular atrophy can develop in severely symptomatic cases.

Enthesopathy, or enthesitis (ie, inflammation of ligament and tendon insertions into bone), is thought to be a characteristic feature of ReA.

The Achilles insertion is the most common site; other sites include the plantar fascial insertion on the calcaneus, ischial tuberosities, iliac crests, tibial tuberosities, and ribs.

Sacroiliitis frequently occurs in adults who are positive for human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–B27 (though it is apparently less common in children).

It is typically self-limiting. Whereas 50% of patients with ReA may develop low-back pain, most physical examination findings in patients with acute disease are minimal except for decreased lumbar flexion.

Patients with more chronic and severe axial disease may develop physical findings similar to, or even indistinguishable from, those of ankylosing spondylitis.

-

Asymmetrical, predominately lower-extremity, oligoarthritis as the major presenting symptom, sometimes with early myalgias

-

Acute onset of ReA, with malaise, fatigue, and fever

-

Arthritis occurs in 95% of patients

-

Varies in severity from week to week, episodes last about 1-4 months

-

First symptoms are pain and swelling of the knees, ankles and feet

-

Usually several joints are involved at once

-

Tendon involvement is common and results in heel, foot and back pain (enthesopathy)

-

Low back ache and morning stiffness (sacroiliitis)

-

Musculoskeletal system - Asymmetric oligoarthritis affecting the weight-bearing joints, predominantly the lower extremity

-

enthesopathy; sacroiliitis

Dactylitis, or sausage-shaped finger: a diffuse swelling of a solitary finger or toe, is a distinctive feature of reactive arthritis

RA’ general features resemble those of ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis, but its characteristic articular distribution allow to accurate diagnosis.

Ankylosing spondylitis: cervical changes are more frequent.

Psoriatic arthritis (PA) distal interphalangeal joint abnormalities in both upper and lower extremities are common. Although sacroiliac and spinal changes are identical in ReA and PA, in the latter the incidence and severity of sacroiliac and spinal changes and the tendency to involve the cervical spine are greater.

Radiographic features

ReA can have a very similar appearance to psoriatic arthritis with the classic features of ill-defined erosions, enthesopathy, bone proliferation, early juxta-articular osteoporosis, uniform joint space loss and fusiform soft tissue swelling. However, the distribution is slightly different. Where hand involvement is the most common site in patients with psoriatic arthritis, hand involvement with reactive arthritis is very uncommon .

Eyes

Ocular involvement occurs in about 50% of men with urogenital reactive arthritis syndrome and about 75% of men with enteric reactive arthritis syndrome. Eye involvement typically occurs early in the course of reactive arthritis, as conjunctivitis and uveitis and symptoms (redness of the eyes, eye pain and irritation, or blurred vision) may come and go.

Conjunctivitis(mild bilateral conjunctivitis) is a component of the original triad and is one of the hallmarks of the disease, reported to appear in 33-100% of patients. It tends to occur early in the disease, especially during the initial attack; it may be missed if patients are seen only during subsequent attacks.

An intense red, velvetlike conjunctival injection characterizes the conjunctivitis. Bilateral involvement is common. Edema and a purulent discharge are not rare. The conjunctivitis may be mild and painless or may cause severe symptoms with blepharospasm and photophobia. It usually resolves spontaneously within 2 weeks. In addition to conjunctivitis, ophthalmologic symptoms of ReA include erythema, burning, tearing, photophobia, pain, and decreased vision (rare).

Anterior uveitis (including iritis, iridocyclitis, or cyclitis) is the second most common ocular finding. Iridocyclitis may be the initial ocular manifestation in some patients. Uveitis may occur in 12-37%(or possibly as many as 50%) of patients with ReA and is more frequently found in patients with HLA-B27 and those with sacroiliitis.

At clinical examination, redness, pain, impaired vision, and exudation with hypopyon can suggest iritis. Rarely, an ReA patient may have permanent visual loss from macular infarction or foveal scarring.

A particularly serious ocular manifestation is recurrent nongranulomatous iridocyclitis. Recurrences are usually associated with an acute iridocyclitis that has a rapid onset with conjunctival and episcleral edema and injection. The corneal endothelium has cellular debris and poorly defined, small- to medium-sized keratic precipitates. Heavy flare and cells and a very early tendency toward formation of posterior synechiae are characteristic, more so than in most other forms of acute iridocyclitis.

Spillover vitreitis may be more common in patients with reactive arthritis than those with ankylosing spondylitis.

Other ocular findings that may be noted in ReA include the following:

-

Scleritis

-

Episcleritis

-

Keratitis - Rarely (4% of cases), patients may develop a punctate epithelial keratitis that may lead to central loss of the corneal epithelium and subepithelial infiltrates

-

Cataracts - Lens clouding and posterior subcapsular cataracts occur with prolonged or repeated episodes

-

Hypotony - This may occur after a severe or prolonged course and may persist after resolution

-

Glaucoma - Secondary open-angle glaucoma may occur because of the anterior chamber reaction and the trabecular obstruction or trabeculitis; it usually resolves with aggressive anti-inflammatory therapy; with repeated recurrences, damage to the trabecular meshwork may occur, resulting in secondary glaucoma

-

Corneal ulceration

-

Disc or retinal edema

-

Retinal vasculitis

-

Optic neuritis

-

Dacryoadenitis (occurs rarely in the setting of chlamydial urethritis)

-

Conjunctivitis; anterior uveitis; keratitis; scleritis; episcleritis; cataracts; hypotony; glaucoma; corneal ulceration; disc or retinal edema; retinal vasculitis; optic neuritis; dacryoadenitis

Physical findings in skin and mucous membranes include the following:

Dermatologic manifestations are common, including keratoderma blenorrhagicum, circinate balanitis, nail changes and oral lesions.

Skin and mucocutaneous lesions are commonly observed in ReA: the incidence is variably reported between 8 and 31% of all cases. A much lower incidence (about 1%) in post-dysenteric cases.

Cutaneous involvement include the palms of the hands and soles of the feet (but may extend up the fronts of the legs) and is typified by keratoderma blennorrhagicum. It usually develops 1-2 months after the onset of arthritis, but may accompany or rarely precede the initial manifestations.

It is characterized by keratotic papules and plaques that are painful under pressure. The initial lesion is a dull red macule which rapidly becomes papular and pseudovesicular. Its color changes from yellow to orange-red as the roof thickens to form a hyperkaratotic plaque. The mature lesion may stand out a centimeter or so from the skin surface. Keratoderma is often self-limiting, lasting weeks or months .

The presence of keratoderma blennorrhagica is diagnostic of reactive arthritis in the absence of the classical triad.

Other body surface areas can less commonly affected as the extensor surfaces of the legs, the dorsal aspects of the toes, feet, hands, fingers, nails and scalp.