EBOLA

Luciano Schiazza M.D.

Dermatologist

c/o InMedica - Centro Medico Polispecialistico

Largo XII Ottobre 62

cell 335.655.97.70 - office 010 5701818

www.lucianoschiazza.it

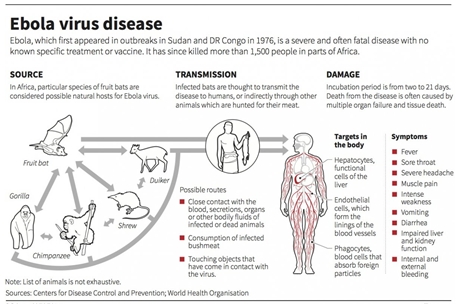

Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF) or Ebola virus disease (EVD) is disease transmitted to humans by direct contact with infected live or dead animals, and more specifically with their body fluid (saliva, blood, urine, or feces of an infected animal). The virus can spread afterward between people through contact with body fluids from an infected person. EVD is a severe, often fatal illness, marked by severe bleeding (hemorrhage), organ failure and in many cases, death in humans and nonhuman primates (such as monkeys, gorillas, and chimpanzees).

These lesions correspond to small painless infarcts of the nail fold due to mild necrotizing vasculitis. Typically these lesions are not associated with systemic signs of vasculitis.

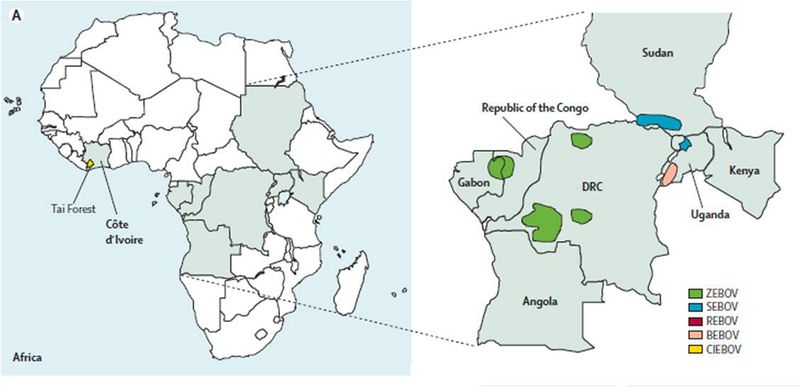

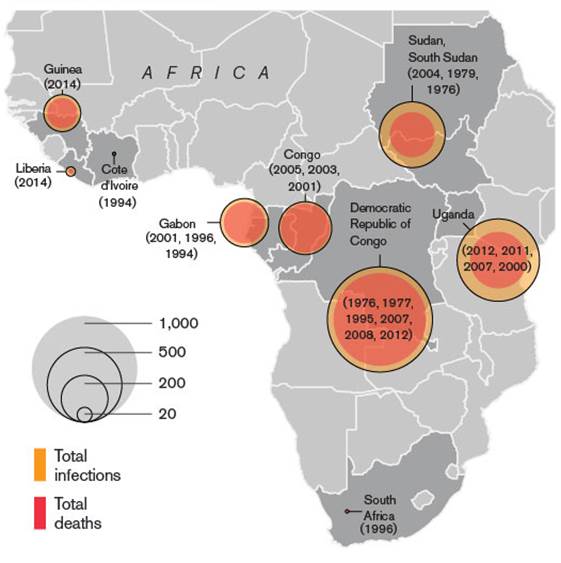

Ebola first appeared in 1976 in 2 simultaneous separate outbreaks: first in Nzara, southern Sudan, and in Yambuku, northern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo). The latter was in a village situated near the Ebola River, from which the disease takes its name. The way in which the virus first appears in a human at the start of an outbreak has not been determined. However, it has been hypothesized that the first patient becomes infected through contact with an infected animal. Since then, outbreaks have appeared sporadically. Ebolavirus is 1 of 3 members of the Filoviridae family (filovirus), along with genus Marburgvirus and genus Cuevavirus. Genus Ebolavirus comprises 5 distinct species of which 4 are pathogenic to humans. The Reston subtype infects only nonhuman primates:

- Zaire ebolavirus (ZEBOV);

- Sudan ebolavirus (SEBOV);

- Taï Forest virus (TAFV) (from Tai National Park, Ivory Coast)(formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus- CIEBOV) was isolated in 1994 from an infected ethnologist who had done a necropsy on a chimpanzee from the Tai Forest;

- Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BEBOV) (from the Bundibugyo district in Uganda), was isolated in 2007;

- Reston ebolavirus (REBOV) (from Reston, Virginia) has origins in the Philippines. It was first discovered in a quarantine facility for Cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) in Reston, VA, USA, headquarter of Hazelton Laboratories, and made popular by Richard Preston's best-selling novel The Hot Zone. Luckily for the monkey caretakers, this is the only strain that is non-pathogenic in humans. Recently, Reston Ebola virus has been found infecting pigs in the Philippines (REBOV).

BDBV, EBOV, and SUDV have been associated with large EVD outbreaks in Africa, whereas RESTV and TAFV have not. The RESTV species, found in Philippines and the People’s Republic of China, can infect humans, but no illness or death in humans from this species has been reported to date. Paleovirus (genomic fossils) of filoviruses (Filoviridae) found in mammals indicate that the family itself is at least tens of millions of years old. Fossilized viruses that are closely related to ebolaviruses have been found in the genome of the Chinese hamster. Rates of genetic change are 100 times slower than influenza A in humans, but on the same magnitude as those of hepatitis B.

The most deadly form is the Zaire subtype, with the natural reservoir for the virus believed to be the fruit bat. The virus has also been found in porcupines, primates, and wild antelope.

Infection with Ebola virus in humans is incidental because humans do not "carry" the virus.

The incubation period (the time from infection to onset of symptoms) is 2 to 21 days.The majority of patients become symptomatic after 8-9 days. Symptoms usually begin abruptly with:

-

Fever, often as high as 103°-105° F;

-

Sore throat,

-

Headache,

-

Intense weakness,

-

muscle pains.

After 1-2 days follow

-

Nausea,

-

Vomiting,

-

Diarrhea.

Patients with more severe symptoms develop in as soon as 24-48 hours coagulopathy with thrombocytopenia, leading to bleeding from the nasal or oral cavity, along with hemorrhagic skin blisters. The development of renal failure, leading to mulisystem organ failurre along with disseminated intravascular coagulation, can then rapidly ensue over 3-5 days, along with significant volume loss.

Patients who develop a fulminant course often die within 8-9 days. Those who survive beyond 2 weeks have a better prognosis for survival.

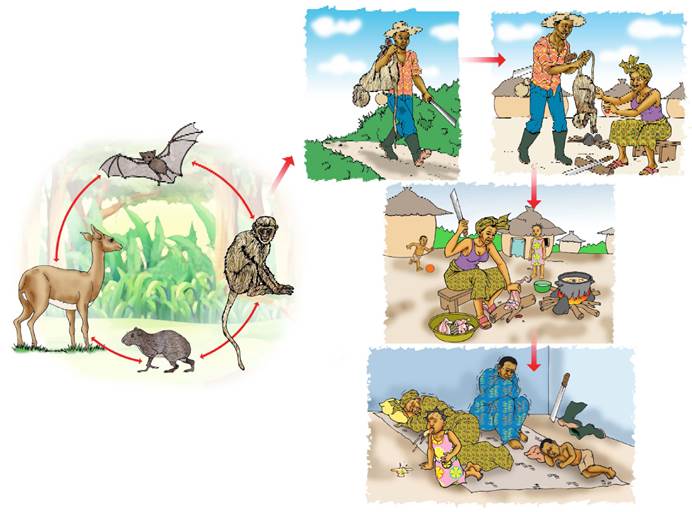

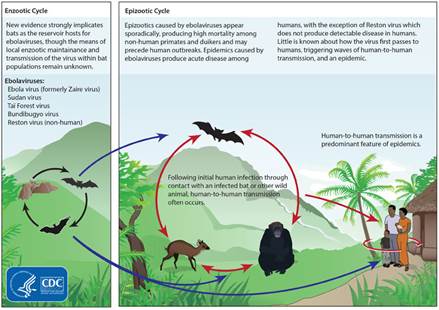

Natural host of Ebola virus

The natural reservoir host of ebolaviruses remains unknown. However, in Africa, fruit bats, particularly species of the genera Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata, are considered possible natural hosts for Ebola virus. As a result, the geographic distribution of Ebolaviruses may overlap with the range of the fruit bats.

Fruit bats can carry it without developing clinical signs of the disease. The virus is killed when meat is cooked at a high temperature or heavily smoked, (people in West Africa usually eat fruit bats dried or in a spicy soup) but anyone who handles, skins or butchers an infected wild animal is at risk of contracting the virus.

Although non-human primates have been a source of infection for humans, they are not thought to be the reservoir but rather an accidental host like human beings.

Since 1994, Ebola outbreaks from the EBOV and TAFV species have been observed in chimpanzees and gorillas.

Risk factors and categories

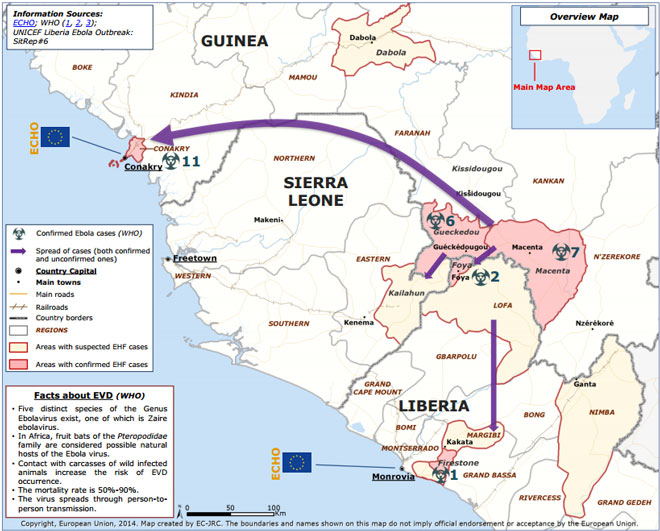

EHF should be suspected in febrile persons who, within 3 weeks before onset of fever, have either

1) traveled in the specific local area of a country where EHF has recently occurred.

In Africa, confirmed cases of Ebola HF have been reported in:

-

Guinea

-

Liberia

-

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

-

Gabon

-

South Sudan

-

Ivory Coast

-

Uganda

-

South Africa (imported)

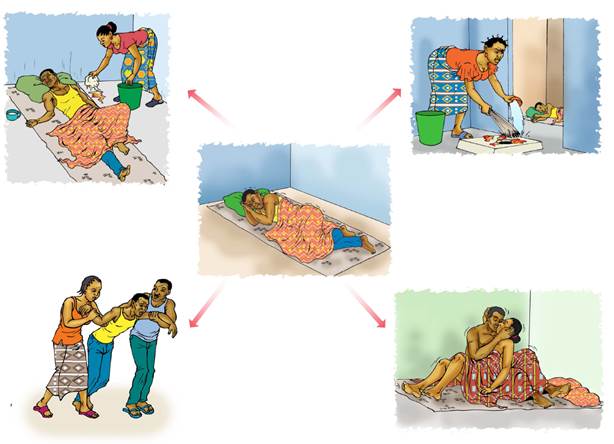

2) had direct unprotected contact with blood, other body fluids, secretions, or excretions of a infected person or animalinfected with Ebolavirus.

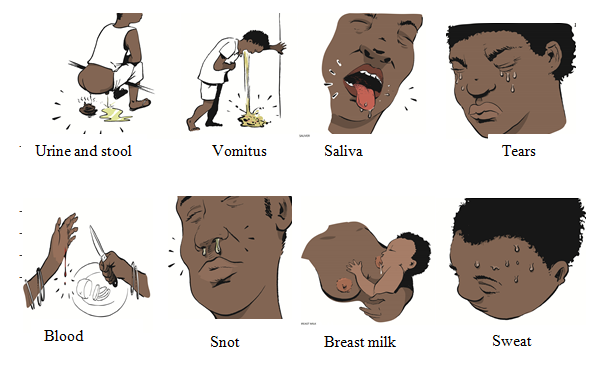

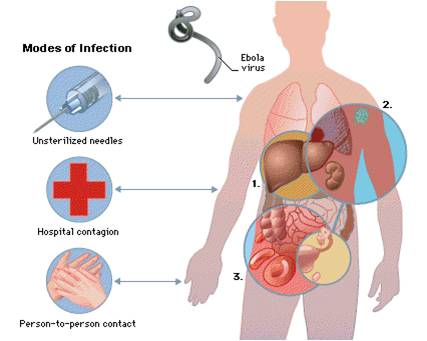

Family members are often infected as they care for sick relatives. Medical personnel also can be infected if they don't use protective gear, such as surgical masks and gloves. In Africa, transmission of Ebolavirus in healthcare settings has been associated with reuse of contaminated needles and syringes and with provision of patient care without appropriate barrier precautions to prevent exposure to virus-containing blood and other body fluids (including vomitus, urine, and stool). About body fluids the virus is in much higher concentration in vomit, blood, and diarrhea compared with saliva, sweat, and tears.

3) had a possible exposure when conducting animal research in a laboratory that handles monkeys imported from Africa or the Philippines.

4) prepared people for burial. The bodies of people who have died of Ebola hemorrhagic fever are still contagious, because the virus may be on the skin. Furthermore, some traditional burial customs, whereby all mourners touch the body, also causes the virus to spread

5) eaten infected “bush meat” – usually monkeys that have already been infected.

Bushmeat is meat from wild animals hunted in Africa, Asia, and South America. The term has particularly been used to refer to meat from animals in West and Central Africa including non-human primates (chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos).

Great apes may harbour Ebola virus that might spread to humans by handling the meat and consumption of such primates.

6) had contact faeces or urine of fruit bats.

Ebola can be passed on if a man who has recovered from the disease has sex within seven weeks because the virus stays alive in sem

The likelihood of acquiring EVD is considered low in persons who do not meet any of these criteria. Even following travel to areas where EHF has occurred, persons with fever are more likely to have infectious diseases other than EHF (e.g., common respiratory viruses, endemic infections such as malaria or typhoid fever).

The risk for person-to-person transmission of hemorrhagic fever viruses is greatest during the latter stages of illness when virus loads are highest; latter stages of illness are characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, shock, and, in less than half of infected patients, hemorrhage. No EHF infection has been reported in persons whose contact with an infected person occurred only during the incubation period (i.e., before onset of fever).

In studies involving nonhuman primates, monkeys could be infected by mechanically generated small-particle aerosols, but epidemiologic studies in humans do not indicate that EHF is readily transmitted from person to person by the airborne route. Although unproven, nevertheless airborne transmission of VHF is a hypothetical possibility during procedures that may generate aerosols.

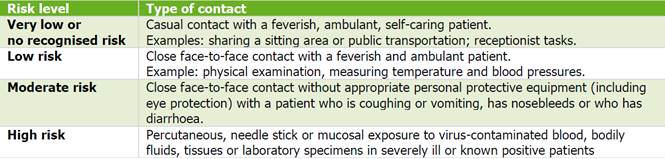

The risk of getting infected with Ebola virus according to type of contact with a human case is summarised in Table below.

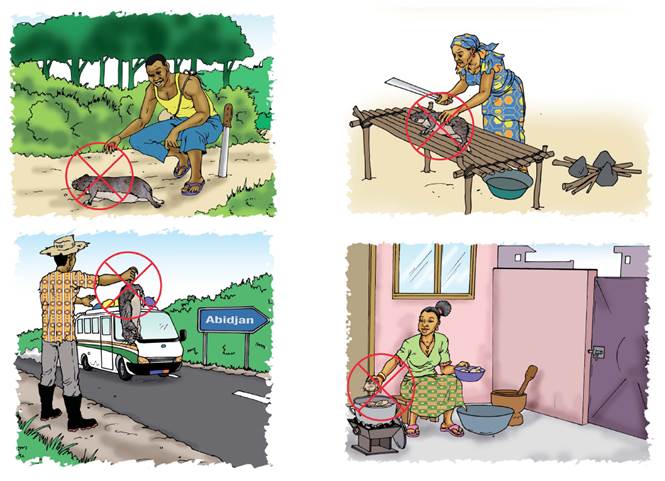

Rural communities that hunt for bushmeat or meat obtained from the forest need clear advice about

- the transmission risk from wildlife,

- the need not to touch dead animals or to sell or eat the meat of any animal they find already dead,

- the risk of human-to-human trasmission

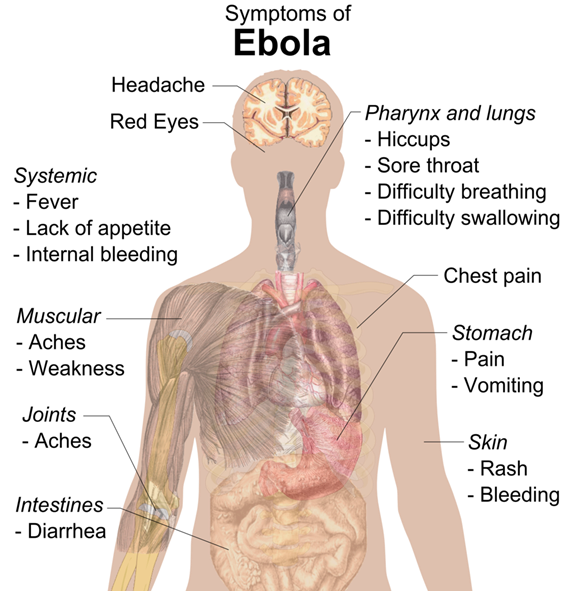

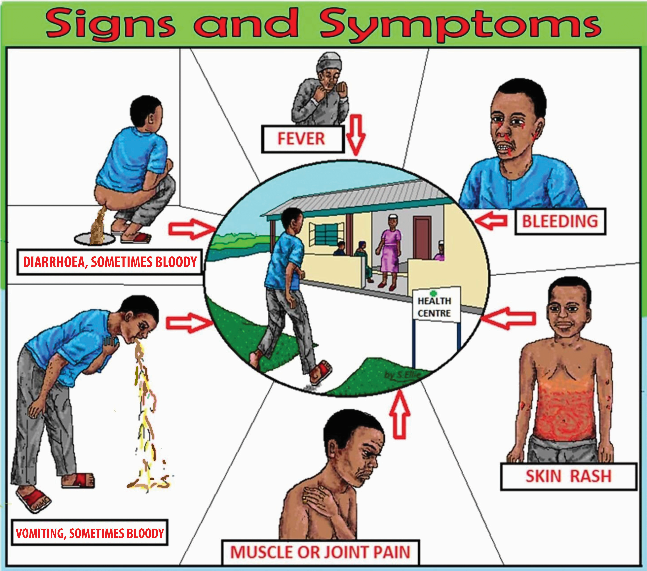

Signs and symptoms

One of the reasons that Ebola is so dangerous is that its symptoms are varied and appear quickly, yet resemble those of other viruses so much that the hemorrhagic fever is not rapidly diagnosed.

Generally, EVD is characterized by the abrupt onset of symptoms (high fever, chills and myalgia) following an incubation period (time interval between contact with the virus and the onset of symptoms) that can vary from two to 21 days (though four to ten days is more common).

Sudden and early symptoms include flu-like stage characterized by

-

fever (high),

-

joint and muscle pain (myalgia),

-

fatigue (weakness),

-

headache (severe)

-

chills

-

sore throat and trouble swallowing,

-

hiccups

The unfortunate thing about these symptoms (before the disease progresses to the bleeding phase) is that they are easily mistaken for

-

malaria,

-

cholera,

-

typhoid fever,

-

dysentery,

-

influenza,

-

various bacterial infections,

-

other tropical fevers

all of which are far more common in regions where Ebola is prevalent.

By the second week of the infection, the patient will either experience a full recovery or undergo systemic multiorgan failure. The Ebola virus spreads through the blood, multiplying in many organs. It causes severe damage to the liver, lymphatic system, kidneys, ovaries, and testes. Platelets and linings of arteries are severely damaged, which results in profuse bleeding. Mucosal surfaces of the stomach, heart membrane, and vagina are also affected.

As the disease progresses, symptoms become increasingly severe and between 40-50% of the patients develop hemorrhagic manifestations (bleeding problems) (between days five and seven):

-

Nausea

-

Stomach pain

-

Hematemesis (vomiting blood up from the stomach)

-

Loss of appetite (anorexia),

-

Diarrhea (bloody)

-

Reddening of the eyes (conjunctival hemorrhages),

-

Nosebleeds,

-

Petechiae,

-

Hematomas (especially around needle injection sites),

-

Ecchymosis,

-

Puncture bleedings,

-

Maculopapular rash (in about 50% of cases),

-

Chest pain, cough, shortness of breath

-

Hemoptysis (spitting up blood from the lungs)

-

Severe weight loss

-

Bleeding, usually from the eyes, and bruising (people near death may bleed from other orifices, such as ears, nose and rectum)

As the virus progresses, bleeding in the brain can lead to severe depression, seizures and delirium.

Heavy bleeding is rare and is usually confined to the gastrointestinal tract (from the mouth and rectum) sometimes leading to the sloughing of the gut and venting from the anus.

In general, the development of bleeding symptoms often indicates a worse prognosis and can result in death.

Patients in the final stage of disease die in the clinical picture of tachypnea, anuria, complete exhaustion (prostration), hypovolemic shock and multi-organ failure.

Chief Epidemiologist Philippe Calain from the CDC Special Pathogens Branch sums up the appearance of his patients during the 1995 Ebola outbreak in Kikwit (Democratic Republic of the Congo):

"At the end of the disease the patient does not look, from the outside, as horrible as you can read in some books. They are not melting. They are not full of blood. They're in shock, muscular shock. They are not unconscious, but you would say 'obtunded', dull, quiet, very tired. Very few were hemorrhaging. Hemorrhage is not the main symptom. Less than half of the patients had some kind of hemorrhage. But the ones that had bled, died"

Subsequent signs of indicate multisystem involvement:

-

gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea),

-

respiratory (chest pain, cough)

-

neurological (headache) manifestations.

People are infectious as long as their blood and secretions contain the virus. Ebola virus was isolated from semen 61 days after onset of illness in a man who was infected in a laboratory.

Laboratory findings include low white blood cell and platelet counts and elevated liver enzymes.

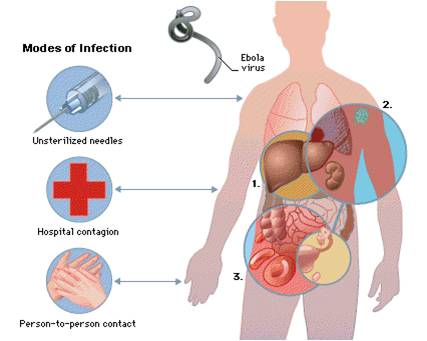

Transmission

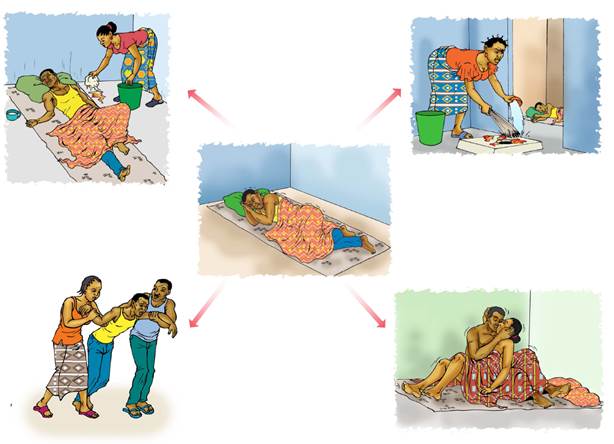

The risk for person-to-person transmission of hemorrhagic fever viruses is greatest during the latter stages of illness when virus loads are highest; latter stages of illness are characterized by vomiting, diarrhea, shock, and, in less than half of infected patients, hemorrhage.

No VHF infection has been reported in persons whose contact with an infected person occurred only during the incubation period (i.e., before onset of fever).

Infected people typically don't become contagious until they develop symptoms.

It has been hypothesized that the first patient becomes infected through contact with an infected animal’s bodily fluids (blood, vomitus, urine, and stool). When an infection does occur in humans, there are several ways in which the virus can be transmitted to others. These include:

-

direct contact with the blood or secretions of an infected person

-

exposure to objects (such as needles) that have been contaminated with infected secretions. The virus is in much higher concentration in vomit, blood, and diarrhea compared with saliva, sweat, and tears, making disinfection of public areas such as restrooms imperative in order to contain the virus.

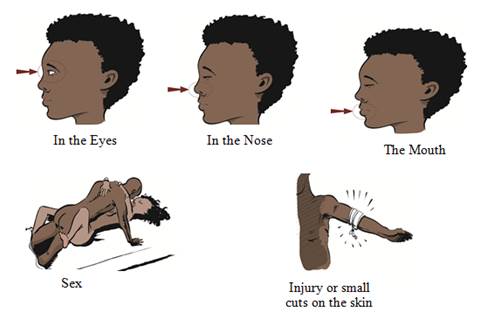

A person can be infected if any of the above liquid(s) goes into his/her body by: the eyes, nose, mouth, sex, or injury on the skin.

The Ebola virus enters the host primarily through mucosal surfaces or skin abrasions, with most human infections occurring after direct contact with patients or cadavers with blood, secretions, organs or other biological fluids from an infected person.

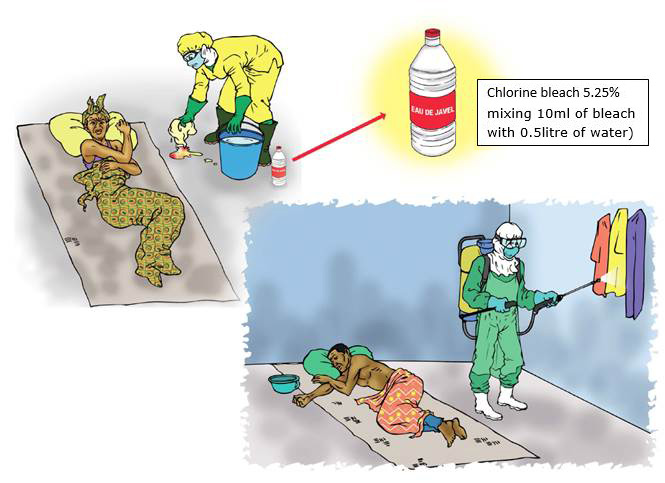

Embalming of an infected dead person (according local traditional burials rituals and ceremonies in which mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased person and handle these corpses) can also play a role in the transmission of Ebola.

Transmission to humans can also occur by contact with dead or living infected animals: hunting, handling and butchering of wildlife e.g. primates (such as monkeys and chimpanzees), forest antelopes, duikers, porcupines and bats.

Family members are often infected in the course of feeding, holding, or otherwise caring for sick relatives, because coming into close contact with secretions of infected person or with objects, such as needles, that have been contaminated with infected secretions.

Ebola virus may be transmitted in clinics or hospitals in Africa where appropriate practices of basic hygiene and sanitation are low. Medical centers in Africa are often so poor that they must reuse needles and syringes. Some of the worst Ebola epidemics has been associated with reuse of contaminated injection equipment (not sterilized between uses) and with provision of patient care without appropriate protective gear.

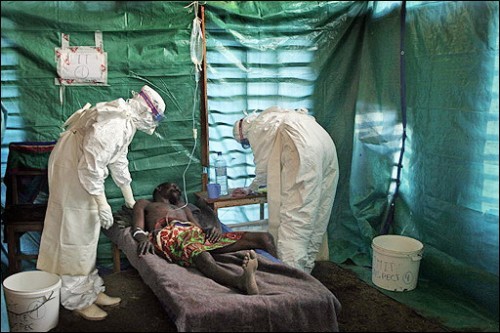

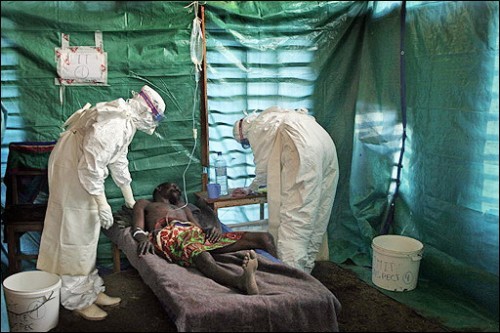

Transmission to health-care workers has been reported when appropriate infection control measures have not been observed. These measures include

-

the wearing of protective clothing, such as face protection (face shield, medical masks, goggles), clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures);

-

the use of infection-control measures, including complete equipment sterilization;

-

the isolation of Ebola fever patients from contact with unprotected persons.

Because it is not always possible to identify patients with EBV (early initial symptoms may be non-specific), it is important that health-care workers apply standard precautions consistently with all patients – regardless of their diagnosis – in all work practices at all times.

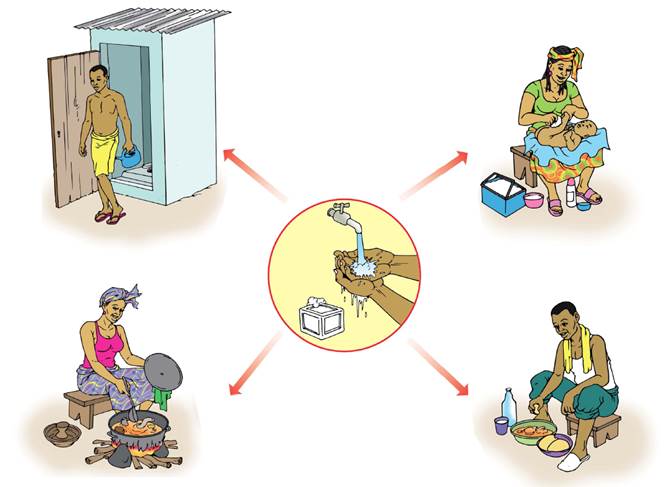

These include

-

basic hand hygiene,

-

respiratory hygiene,

-

the use of personal protective equipment (according to the risk of splashes or other contact with infected materials),

-

safe injection practices (disposable instruments, such as needles and syringes, is also important. If instruments are not disposable, they must be sterilized before being used again),

-

proper cleaning of contaminated environment,

-

safe burial practices.

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from suspected human and animal Ebola cases for diagnosis should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories.

Transmission through oral exposure and through conjunctiva exposure is likely and has been confirmed in non-human primates.

There is limited evidence of airborne transmission in any human epidemics. The virus is not spread by breathing the air, it is not airborne unless the infected person coughs or sneezes on you.

Bats drop partially eaten fruits and pulp, then land mammals such as gorillas and duikers feed on these fallen fruits. This chain of events forms a possible indirect means of transmission from the natural host to animal populations In Africa.

Men who have recovered from the disease can still transmit the virus through their semen for up to 7 weeks after clinical recovery

EBOV can survive in liquid or dried material for a number of days . However, EBOV can be inactivated by UV radiation, gamma irradiation, heating for 60 minutes at 60 °C or boiling for five minutes. The virus is susceptible to sodium hypochlorite and disinfectants.

Freezing or refrigeration will not inactivate Ebola virus.

There's no evidence that Ebola virus can be spread via insect bites

Complications

Ebola hemorrhagic fevers leads to death for a high percentage of people who are affected. As the illness progresses, it can cause:

-

Multiple organ failure

-

Severe bleeding

-

Jaundice

-

Delirium

-

Seizures

-

Coma

-

Shock

For people who survive, recovery is slow. It may take months to regain weight and strength, and the viruses remain in the body for weeks. People may experience:

-

Hair loss

-

Sensory changes

-

Liver inflammation (hepatitis)

-

Weakness

-

Fatigue

-

Headaches

-

Eye symptoms (Iritis, iridociclitis, choroiditis, blindness)

-

Testicular inflammation

EBOV and SUDV may be able to persist in the semen of some survivors for up to seven weeks, which could give rise to infections and disease via sexual intercourse.

Reservoir

In Africa, fruit bats, particularly species of the genera Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata, are considered the most likely natural reservoir for Ebola virus. The geographic distribution of Ebolaviruses may overlap with the range of the fruit bats.

Bats were known to reside in the cotton factory in which the first cases for the 1976 and 1979 outbreaks were employed, The absence of clinical signs in these bats is characteristic of a reservoir species. Antibodies against Ebola Zaire have been found in fruit bats in Bangladesh, thus identifying potential virus hosts and signs of the filoviruses in Asia.

Traces of EBOV were detected in the carcasses of gorillas and chimpanzees or duiker since 1994. However, the high lethality from infection in these species makes them unlikely as a natural reservoir. But handling the carcasses could become the source of human infections.

Fruit bats are also eaten by people in parts of West Africa where they are smoked, grilled or made into a spicy soup

Transmission between natural reservoir and humans is rare, and outbreaks are usually traceable to a single case where an individual has handled the carcass of infected gorilla, chimpanzee, or duiker.

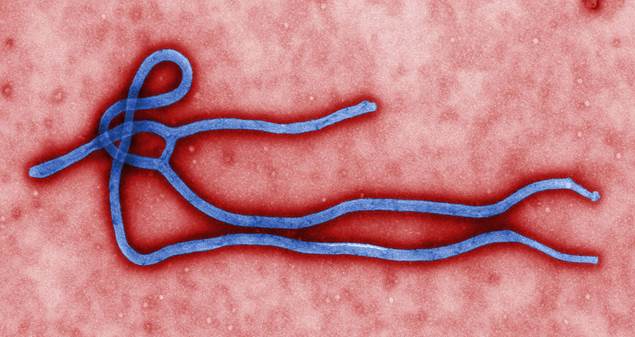

Virology

Ebola virus is a membre of Filoviridae, a family of viruses that contain single, linear, negative-sense ssRNA genomes. The family name was derived from the Latin word filum, which alludes to the thread-like appearance of the virions when viewed under an electron microscope.

Filoviruses have been divided into two genera: Ebola-like viruses with species Zaire, Sudan, Reston, Cote d’Ivoire and Bundibugyo; and Marburg-like viruses with the single species Marburg. All of these are responsible for hemorrhagic fevers in primates that are characterized by often fatal bleeding and coagulation abnormalities.

Ebolavirions are filamentous particles that may appear in the shape of a shepherd's crook or in the shape of a "U" or a "6", and they may be coiled, toroid, or branched. In general, Ebolavirions are 80 nm in width, but vary somewhat in length.

Ebola virus replicates in 8 hours: therefore, it spreads rapidly.

Diagnosis

One of the difficulties and the unfortunate thing encountered in identifying Ebola virus is that in the early days of the disease, the symptoms are varied and appear quickly, similar to those of other types of infectious diseases (high fever, chills and myalgia), and are easily mistaken for malaria, Lassa fever, typhoid fever, influenza, cholera, shigellosi, leptospitosis, plague, relapsing fever and even meningitis, etc., all of which are far more common in regions where ebola is prevalent, but also less fatal. Only after 3-5 days (or even later in the course of the disease) the successive signs, hallmark of the illness, become evident.

The medical history, especially travel and work history along with exposure to wildlife are important to suspect the diagnosis.

The diagnosis of EVD is confirmed definitively in a laboratory through several types of tests:

-

by isolating the virus by cell culture,

-

detecting viral RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

-

detecting viral proteins by by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA),

-

detecting antibodies against the virus in a persons blood.

During an outbreak, virus isolation is often not feasible. The most common diagnostic methods are therefore real time PCR and ELISA detection of proteins, which can be performed in field or mobile hospitals. Filovirions can be seen and identified in cell culture by electron microscopy due to their unique filamentous shapes, but electron microscopy cannot tell the difference between the various filoviruses despite there being some length differences

Differential diagnosis

The symptoms of EVD are similar to those of Marburg virus disease. It can also easily be confused with many other diseases common in Equatorial Africa such as

-

other viral hemorrhagic fevers,

-

falciparum malaria,

-

typhoid fever,

-

shigellosis,

-

rickettsial diseases such as typhus,

-

cholera,

-

gram-negative septicemia,

-

borreliosis, such as realpsing fever

-

Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) enteritis.

Other infectious diseases should be included in the differential diagnosis:

-

leptospirosis,

-

scrub typhus,

-

plague,

-

Q fever,

-

candidiasis,

-

histoplasmosis,

-

trypanosomiasis,

-

visceral leishmaniosis,

-

hemorragic smallpox,

-

measles,

-

fulminant hepatitis.

Non-infectious diseases that can be confused with EVD are

-

acute promyelocitic leukemia,

-

hemolytic uremic syndrome,

-

snake envenomation,

-

clotting factor deficiencis/platelet disorders,

-

thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura,

-

hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia,

-

Kawasaki disease and even

-

warfarin poisoning.

Prevention

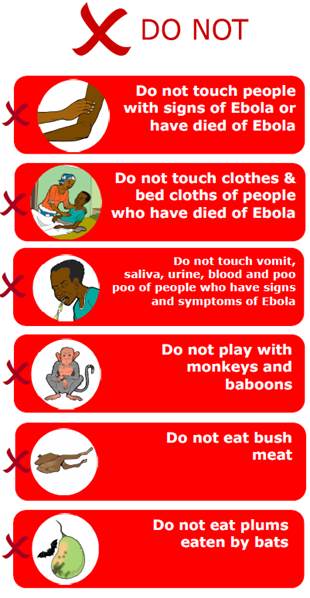

In the absence of effective treatment and a human vaccine, prevention focuses on avoiding contact with the viruses, raising awareness of the risk factors for Ebola infection and taking individual protective measures. These are the only ways to reduce human infection and death.

Prevention includes decreasing the spread of disease reducing the risk of wildlife-to-human transmission from contact with infected fruit bats or monkeys/apes and the consumption of their raw meat. This may be done by checking such animals for infection and killing and properly disposing of the bodies if the disease is discovered. Animals should be handled with gloves and other appropriate protective clothing. Animal products (blood and meat) should be thoroughly cooked before consumption.

Properly cooking meat and wearing protective clothing when handling meat may also be helpful.

As is wearing protective clothing and appropriate personal protective equipment and washing hands when around an infected patients at home. Samples of bodily fluids and tissues from people with the disease should be handled with special caution. Close physical contact with Ebola patients should be avoided.

Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission in the community arising from direct or close contact with infected patients, particularly with their bodily fluids.

Regular hand washing is required after visiting patients in hospital, as well as after taking care of patients at home and daily activity.

Because it is not always possible to identify patients with EBV early as the initial symptoms may be non-specific, health-care workers have to apply , in addition to standard precautions, other infection control measures to avoid any exposure to the patient’s blood and body fluids and direct unprotected contact with the possibly contaminated environment with all patients in all work practices at all times:

-

hand hygiene, (soap and water, or use alcohol-based hand rubs containing at least 60 percent alcohol when soap and water aren't available).

-

personal protective equipment because of the risk of splashes or other contact with infected materials (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles, a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown),

-

use of infection-control measures (complete equipment sterilization, safe injection practices, routine use of disinfectant, safe burial practices avoiding contact with the body of the deceased patient (Traditional burial rituals, especially those requiring embalming of bodies, should be discouraged or modified),

-

isolation of Ebola HF patients from contact with unprotected persons

Tourists and visitors travelling in West African countries or residents in affected areas, should follow some precautions:

-

avoiding contact with symptomatic patients and/or their bodily fluids

-

avoiding contact with corpses and/or bodily fluids from deceased patients

-

avoiding any form of close contact with wild animals (including monkeys/apes, fruit bats, forest antelopes, rodents and bats), both alive and dead, and consumption of any type of ‘bushmeat’

-

avoiding habitats which might be populated by bats such as caves, isolated shelters, or mining sites.

-

washing and peeling fruits and vegetables before consumption

-

strictly practising ‘safe sex’

-

strictly following hand-washing routines

-

animals should be handled with gloves and appropriate protective clothing,

-

animal products (blood and meats) should be thoroughly cooked before consumption

Epidemiology

The disease typically occurs in outbreaks in tropical regions of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The name of the disease originates from one of those first recorded outbreaks in 1976 in Yambuku, Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Zaire), which lies on the Ebola River. The first recorded outbreak of Ebola occurred in Sudan (due to the so called Ebola Sudan subtype), near the border with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, between June and November 1976(August and November 1976), an outbreak due to E. Zaire occurred in DRC, near the borders with Sudan and the Central African Republic.

The Ebola virus was first associated with an outbreak of 318 cases of a hemorrhagic disease in Zaire. Of the 318 cases, 280 of them died—and died quickly. That same year, 1976, 284 people in Sudan also became infected with the virus and 156 died.

The largest outbreak to date is the ongoing 2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak, which is affecting Guinea, Sierra Leona and Liberia.

In February 2014, a strain of the Ebola Virus appeared for the first time in Guinea. Then other cases have been reported in Liberia and in Sierra Leone.

Two American medical providers, Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol were exposed while treating infected patients in Liberia. Both were trasported via speciality aircraft into Emory University Hospital the first US hospital to care for patients exposed to Ebola and treated with ZMapp, an experimental drug not yet been tested in humans for safety or effectiveness. The product is a combination of three different monoclonal antibodies that bind to the protein of the Ebola virus.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for the disease. No licensed vaccine for EVD is available.

Patients receive supportive therapy. This consists of balancing the patient's fluids and electrolytes, maintaining their oxygen level and blood pressure, and treating them for any complicating infection